Download All Country Data

In any epidemic, those on the frontlines — the health care workers — carry the greatest burden. They are both infected and affected, facing not only a disproportionately high risk of illness and death but also suffering isolation and even stigma, whether in their communities or by their governments. Often, they are forced to work without the resources they need to do their jobs. It’s crucial to protect them, as we urgently called for in our January 2021 report.

When COVID-19 struck, Resolve to Save Lives partnered with ministries of health and organizations in 22 African countries to develop and implement an emergency response initiative to improve health care worker safety. Part of the initiative focused on one critical intervention: strengthening infection prevention and control (IPC) measures at the primary health care level.

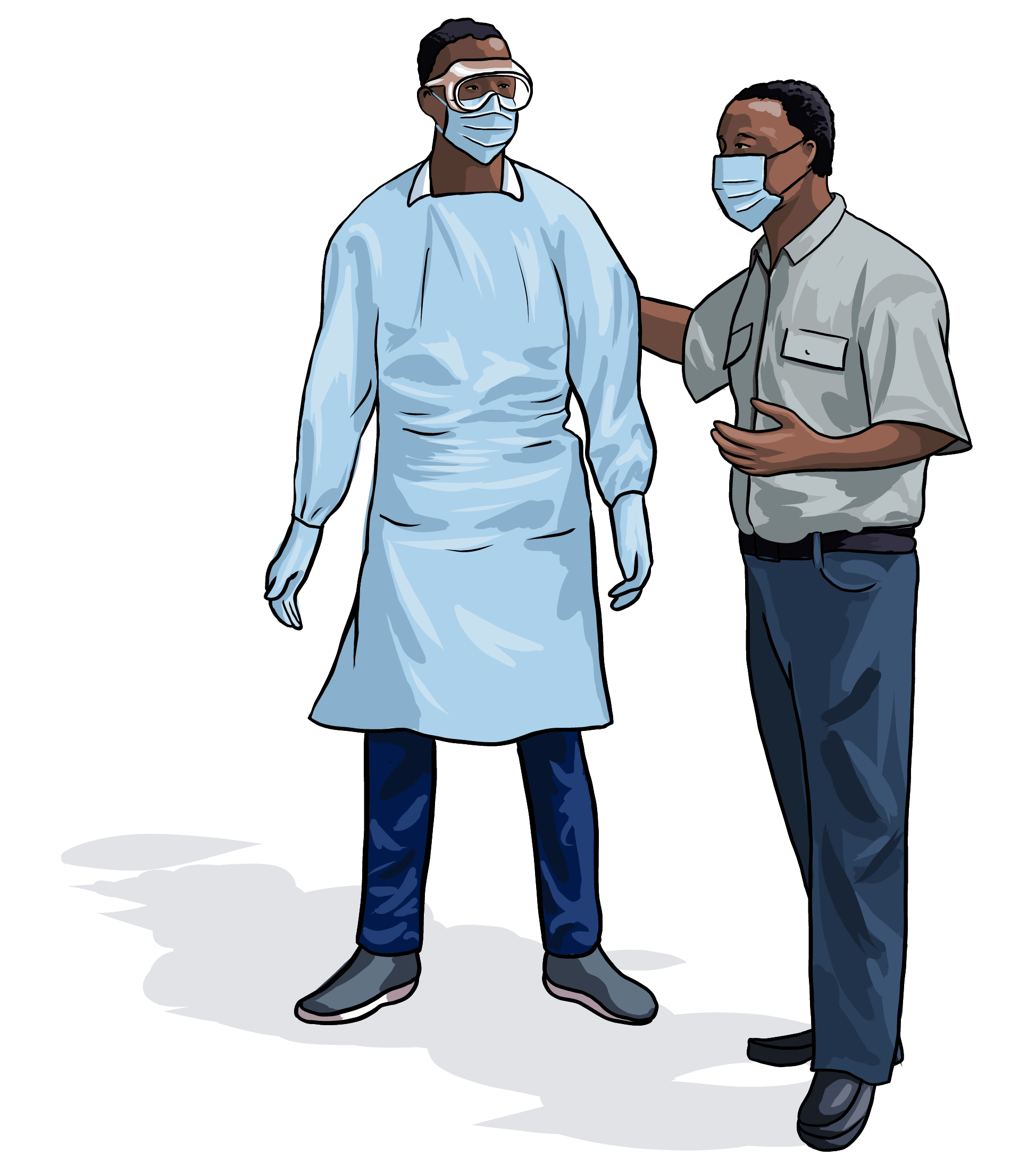

IPC measures in health centers keep patients and health care workers safe from avoidable infections. Such measures include screening and triage of patients, the use of personal protective equipment and social distancing when necessary. When a novel disease pathogen emerges, it may require specific IPC measures; COVID-19 requires different personal protective equipment than Ebola, for example.

To do their jobs safely, health care workers need to be quickly trained in and develop working knowledge of new measures — all the while dealing with the grim reality of a public health emergency. Without adequate IPC, health care workers are unable to do their jobs, which can disrupt essential health services and cause breakdowns in care — particularly in times of crisis.

IPC is, thus, about people — equipping health care workers with tools and strategies to protect themselves and their patients while delivering care. Below, health care workers from RTSL’s implementing partners Last Mile Health and Jhpiego provide a window into their challenges and successes in promoting IPC measures during the COVID-19 pandemic. These are the faces of IPC.

Shirley Seckey-Fahnbulleh

IPC Specialist (Liberia)

“If we take IPC into practice, we are going to save a lot more money and a lot more lives.”

With 20 years of experience as a nurse, Shirley Seckey-Fahnbulleh has worked through two epidemics: first Ebola, and now COVID-19.

During the West Africa Ebola virus epidemic — which claimed nearly 5,000 lives in Liberia in 2014 and 2015 — she learned about and developed a passion for the importance of IPC in keeping patients and health care workers safe from infectious diseases.

“I came to know about IPC during the heat of Ebola, seeing how my colleagues die, how people got sick,” Seckey-Fahnbulleh said. “That didn’t stop me from continuing working in the community to keep education, to work with my colleagues, making sure that they follow IPC standards and protocols.”

Her specialty in nursing is education, and for the past four years she’s worked in infectious disease and control. She currently serves as an IPC specialist with Last Mile Health and is based in Montserrado County, Liberia’s most populated county and home to Monrovia, the nation’s capital. In this role, she provides technical support and supervision to district- and county-level health teams in IPC measures. Whenever she sees a health care worker not practicing proper measures, she mentors them.

“We talk with the facility-based team on how we can bridge those gaps,” Seckey-Fahnbulleh said. “They are involved, and the reason why we are doing that is to ensure that they are a part of the decision. Because if they are part of the decision or the action that’s being taken, they’re going to own it. That’s going to help us promote IPC practices.”

When COVID-19 hit, Seckey-Fahnbulleh sought out information about the emerging virus to help educate her community and fellow health care workers. For example, her team incorporated COVID-19 information into the morning educational forum it operated at clinics. She also disseminated information through her IPC-focused Facebook page and through her community — whether at her daughter’s school, at church or in conversation with neighbors on the street.

“Everywhere I can spread a message, we are doing so, so that the community is keeping safe,” Seckey-Fahnbulleh said.

One shortcoming in IPC measure adherence she has observed is in patient screening, before a patient is allowed entry into the health care setting. In a time of public health crisis, she says, all patients should be screened for infectious diseases — not just those who might appear sick.

“In that way, we are protecting the community, the patients and ourselves,” she said.

In spite of the challenges of working through two public health emergencies, Seckey-Fahnbulleh remains steadfast in her purpose.

“My passion to serve. My passion is to provide the education that I have,” she said.

Menson Z. Kotee

County IPC Supervisor (Liberia)

“In IPC, we say you need to protect yourself while you are saving life. When you are not safe, you can’t save other people.”

During the COVID-19 pandemic, Menson Z. Kotee has seen one major change in his role as an IPC supervisor: more responsibility. But one thing that hasn’t changed is his commitment to his job.

“I’ve been committed from the onset, and with the pandemic, having a passion to save our people, ensuring that we can be able to minimize or curtail this disease,” Kotee said. “We continue to work on a day-to-day basis with increased responsibility. We’re still committed and doing our job.”

As IPC supervisor for the Grand Gedeh County Health Team in Liberia, Kotee coordinates all activities relating to IPC in the county: supervising, coaching and mentoring health care workers; ensuring the IPC supply chain’s continuity to avoid stockout; and providing updates on IPC activity as necessary through weekly meetings. Because Grand Gedeh County is one of the most remote counties in Liberia, this is no small feat.

The pandemic rattled medical supply chains across the world; on top of which, COVID-19 required different PPE than past epidemics. Combined, these shocks to the system led to stockout of valuable IPC materials and left many health care workers without the means to safely give care.

“Some health workers were afraid because they don’t have supply, so they wouldn’t take patients, whether patients were coming for normal services or had COVID,” Kotee said. “If we had had IPC supply from the onset of the pandemic, it would’ve been of great help to us.”

As new information emerged, Kotee also had to educate health care workers about IPC practices for the virus, which were different than those for Ebola due in part to their different modes of transmission — COVID-19 via respiratory fluids, and Ebola via body fluids. Although health care workers require personal protective equipment (PPE) for both viruses, the PPE itself differs substantially.

Following these initial challenges, Kotee and his fellow IPC specialists found ways to manage shortages. They coordinated with one another to assess local supply and see if other areas could provide materials to close the gaps. They also worked with organizations such as Last Mile Health to secure funding and support from donors and the government. Addressing the materials gap not only helped health care workers stay safe, but also may have helped convince patients — many of whom were initially fearful of health facilities as centers for disease spread— to seek care. Through media, his team engaged local communities to assure them that primary care services had not stopped and were being safely delivered.

“People have the belief that if they come to the facility, the facility will give them COVID,” he said. “We are saying, ‘no.’ We are there to serve you.”

Kotee hopes to continue this service by working his way up to the ministry level. There, he can enact effective IPC practices at the policy level that combat the cycle of panic and neglect when it comes to IPC, and instead make it an everyday priority.

“In Liberia, in our health setting, IPC is just something that you do when it’s time for outbreak,” Kotee said. “When there is no outbreak or no pandemic, IPC is just slipping.”

Rita McGill

County IPC Supervisor (Liberia)

“Infection prevention and control is everybody’s business.”

When COVID-19 hit, public health officials scrambled to figure out the preventive measures necessary to help contain it. As the IPC Supervisor for coastal Grand Bassa County, Liberia, Rita McGill saw firsthand the struggle to adapt to the new disease.

Across the county, McGill oversees 35 primary health facilities. Her job involves ensuring proper IPC measures in health facilities, training health care workers and ensuring that IPC supplies meet demand. Duties include ensuring proper screening, triage and — if necessary — isolation measures are in place for patients. McGill, who also has training as a nurse, observes health care workers at each facility. If they make an error, she will advise on the spot.

“Basically, it’s mentorship,” she jokes. “It’s tedious.”

The pandemic increased McGill’s responsibilities. IPC commodities such as hand sanitizer and soap were suddenly in short supply. Health care workers needed to learn a new set of IPC measures for COVID-19 — all the while responding to it in real-time and trying to maintain essential health services. McGill further noted how because COVID-19 could be asymptomatic, it was harder to convince some communities of the reality of the pandemic.

However, she ultimately found her communities receptive to her messages about the virus.

“In the community, people started linking with me because they felt that I could maybe tell them to go to the hospital or to take this drug, because I was a health worker,” she said. “Because I was a health worker, I had means of educating people as an IPC supervisor and nurse.”

“I count myself as a lifesaver,” McGill said.

Samuel Nkrumah

Hospital IPC Lead (Ghana)

“To be able to care for our client, we must first take care of ourselves.”

Samuel Nkrumah thought he’d seen it all — until COVID-19.

A nursing officer at Princess Marie Louise Children’s Hospital in Accra, Ghana, Nkrumah has treated clients with various conditions for the past 10 years. As the hospital’s IPC lead, he saw health workers providing care without strict adherence to IPC standards and appropriate PPE. The situation was indeed worrying, especially when clients and health care workers started testing positive for COVID-19. He was presented with a major test of his career — sustaining service continuity amid a rather uncertain pandemic.

Following training from organizations including Jhpiego, Ghana Health Service and Resolve to Save Lives, Nkrumah and his team organized a series of refresher trainings on hand hygiene, social distancing and how to effectively use PPE.

“I think when orderlies are trained to disinfect surfaces we often touch, it breaks the transmission cycle and prevents COVID-19 infection at the hospital, Nkrumah said.

His team also reevaluated how to treat special needs patients, such as those in child welfare clinics or those receiving treatment for sickle cell disease. To limit potential exposure, his team now recommends such patients visit once every two months, instead of monthly. The hospital has scheduled voice calls to regularly check on such patients and arrange for them to visit when necessary.

Perhaps his biggest takeaway is the importance of health care workers’ emotional well-being. Nkrumah learned that maintaining healthy physical, emotional and mental health makes one more resilient. He now starts his day with a morning devotion, exercise and breakfast, checks his baseline vitals as soon as he gets to the hospital and ends his day with a nutritious meal, steam inhalation and a long respite.

Nohn Korto

Community Health Services Supervisor (Liberia)

“What has remained the same for me during this pandemic is my passion for saving life.”

As a Community Health Services Supervisor, Nohn Korto provides a vital bridge between health facilities and the communities they serve.

Her multi-faceted role includes supervising community health workers, known locally as community health assistants, holding community meetings as needed, and supplying both IPC commodities and medications for children under five years of age. This public-facing role requires a high level of community trust, which she works hard to cultivate. She works in Rivercess County, one of Liberia’s smallest and most remote counties.

“I’m a direct representative of the community to the clinic,” Korto said. “I’m part of them as a community worker, and I’m there to save life, not harm them.”

As one of the first lines of medical information to the community, Korto had an important role to fulfill in the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic. She worked to educate communities about our evolving understanding of the virus — including its signs and symptoms, specific IPC measures and water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) standards — even as cases in the country remained low.

“My biggest challenge as a health care worker in this pandemic is to convince community dwellers that COVID-19 is here in Liberia,” Korto said.

The community trust she cultivated also helped her learn of cases. For example, if a community member began to present the virus’s symptoms, other community members would let her know.

Another challenge the pandemic posed was inadequate PPE. Masks and gloves, for example, were hard to come by initially, which made fighting the virus difficult. Through donor and governmental support, Korto’s communities received more resources.

“We even have towel tissue now,” Korto said. “You don’t have to wipe your hand with the towel again. You can use the towel tissue and put it in the trash.”

Because her role involves so much public interaction, she’s had to limit certain activities during the pandemic to keep everyone safe. These interventions include limiting the number of participants at community meetings to key stakeholders who can further disseminate information as needed, as well as observing COVID-19 protocols such as handwashing and mask-wearing. Despite these changes, she’s been able to maintain the trust required for her to fulfill her role.

“I’m always there for you,” Korto said of her neighbors. “So you can trust me with any information.”

Samuel Adusei

Hospital IPC Lead (Ghana)

“We are dealing with issues of self-contamination and health worker-to-health worker transmission of COVID-19.”

As a mental health nurse and the IPC lead at his local hospital, Samuel Adusei wears many hats.

As a nurse, he provides preventive care through health education and mental health care to patients at Sefwi-Wiawso Hospital in Ghana’s Western North Region. As it did for many health care workers, the COVID-19 pandemic disrupted his routine.

When the pandemic began, Adusei noticed that patients were coming to the facility less and less; he also noticed that some frontline health workers were providing care without adequate knowledge of IPC measures and appropriate PPE. It was not surprising that the first time a patient tested positive for COVID-19, several nurses who cared for the patient also became infected.

As IPC lead, Adusei is charged with informing his fellow health care workers about the results of their COVID-19 tests and encouraging them to take necessary steps to quarantine and receive medical care. Following training from organizations including Jhpiego, Ghana Health Service and Resolve to Save Lives, he refined his approach to IPC measures and organized a refresher training for all departments and wards at the hospital.

“I took the training to heart, because it helped us to deal with the challenges we were facing at the moment,” Adusei said.

Today, every health care worker at the Sefwi Wiawso Hospital is trained to adopt standard precautions, including hand hygiene, social distancing, cough etiquette and appropriate use of PPE such as gloves and face masks.

Learn more about IPC:

Lack of adequate IPC practices and training causes preventable deaths. Improving IPC can keep health care workers safe, protect their mental health and help build stronger health systems. Governments must work towards full implementation of IPC standards by implementing World Health Organization protocols at the national and facility levels. To learn more about how this can be accomplished, read our report, Protecting Health Care Workers: A Need for Urgent Action.

Share your story:

Share your story:

At the end of this @WHO International Year of Health and Care Workers, we want to hear from and highlight the incredible work of health care workers around the world. Do you know any #healthheroes? We’d love to hear from you. Share your story with the hashtag #healthheroes — let’s start a conversation.