About Ebola

Rare but deadly, Ebola Virus Disease is caused by a virus thought to have originated in bats. In recent years, humans have also become reservoirs of the virus,1 spreading it through bodily fluids.2 Although there have been relatively few Ebola outbreaks since the virus was discovered in 1976, they have been devastating, with death rates ranging from 20% to 90%.

Initial symptoms are often flu-like, but can progress to liver and kidney dysfunction and internal and external bleeding.3 Treatments, such as oral or intravenous fluids and monoclonal antibodies, can greatly improve chances of survival.4 Effective vaccines against the Zaire strain of the virus have been available since 2019, but supply remains limited.5 Nonetheless, the World Health Organization (WHO) has been able to coordinate swift vaccine delivery during recent outbreaks.

In 2014-2016 and 2018-2020, gaps in detection and response led to delays that allowed two Ebola outbreaks to become epidemics. The first, in West Africa, began in Guinea and spread to Liberia and Sierra Leone, as well as seven other countries including the United States and Italy, between 2014 and 2016. Subsequent analysis pointed to failures that hampered response efforts.6

In the past decade, two Ebola epidemics claimed nearly 14,000 lives.

In 2014, Guinea lacked a formal emergency response system, a public health agency and trained field epidemiologists.7 Communication about how to limit risk of Ebola spread was poorly handled, leading to resistance, mistrust and the viral spread of misinformation; one rumor held that the virus wasn’t even real.8 That entire parts of the country were simultaneously cordoned off to prevent the spread of disease only added to a culture of fear.9 Border controls to limit spread to neighboring countries were not established until five months after the outbreak had been declared.10 Vaccines were not available at the outset of the outbreak; as the epidemic progressed, only those enrolled in clinical trials could access them. Vaccination rollout was further hampered by misinformation, including that the vaccine made women infertile or men impotent.11

By the time the West Africa Ebola epidemic ended in 2016, approximately 28,600 people had been infected, and 11,325 people had died. The cost to the global economy was estimated to be $53 billion.12

Despite success containing several earlier Ebola outbreaks, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) was hampered from the start in its response in 2018, resulting in an epidemic that lasted until 2020. Due to ongoing regional conflict, the disease surveillance system had broken down. Health care workers were on strike because of a salary payment dispute in May of 2018—the time when investigations later determined the first case of Ebola had emerged.13 As a result, no suspected cases were identified, and no alerts were issued for two months. The outbreak became so large that, at its peak, 16,000 local responders were required, in addition to 1,500 staff sent by WHO and more deployed by other international partners.14 A total of 171 health care workers were infected,15 and in total the epidemic caused about 2,280 deaths among 3,470 diagnosed cases.

In 2021, Ebola outbreaks of the Zaire strain emerged again in both Guinea and DRC under strained circumstances, with each country dealing with multiple infectious disease outbreaks simultaneously—including COVID-19. But the outcomes were drastically different. Guinea’s outbreak was declared over after six months and 12 deaths. And the outbreak in DRC ended after three months and 11 deaths. Vaccines were administered successfully, health care worker infections were limited and neither outbreak spread beyond the region in which it emerged.

What changed?

What Happened in Guinea

On January 18, 2021, a nurse from the N’zérékoré Region of Guinea arrived at a clinic in Gouécké with a headache, vomiting and fever, among other symptoms. She was diagnosed with typhoid and released. Days later, her condition had become so severe that she was admitted to a hospital, where she was diagnosed with malaria and salmonella. Following discharge, however, her condition only worsened. She sought care at a private clinic and subsequently from a traditional healer, to no avail. She died several days later.16

In the week following her February 1 funeral, the woman’s husband and other family members became ill.17 Some family members’ symptoms were recognized as consistent with viral hemorrhagic fever and reported to the national epidemic alert system on February 11. Blood specimens were taken from two hospitalized patients on February 12, and the nearby regional lab confirmed the infections to be Ebola the next day.18 Meanwhile, the woman’s husband had traveled across the country to the capital city of Conakry for treatment, creating potential new exposures. He too was confirmed to have Ebola, and on February 14, the government announced the outbreak.

Amid simultaneous outbreaks of yellow fever, measles, polio and COVID-19, the new Ebola outbreak—undetected for nearly a month—threatened to hit the same region of the country where the massive 2014-2016 Ebola epidemic emerged.

The Response in Guinea

Within 24 hours of the first alert confirming Ebola’s reemergence, Guinea activated national and district emergency operations centers (EOCs) to coordinate containment.19 Since the 2014-2016 Ebola epidemic, Guinea had established the National Agency for Health Security (ANSS) to aid in detecting and stopping outbreaks, and with the support of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and other partners, had established a national EOC as well as 38 EOCs at the district level.20 Furthermore, the country had invested in hiring and training a range of public health officials—from epidemiologist disease detectives to risk communication and community engagement specialists, who could help build trust and combat misinformation—to quickly respond to the outbreak. ANSS provided a centralized coordination hub from which officials could activate an effective response.

The day after the lab tests confirmed Ebola, ANSS deployed teams of staff and partners from key stakeholder organizations to begin thorough case investigation and contact tracing.21,22 The Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (Africa CDC), which was established in 2017 by the African Union, partly in response to the 2014-2016 Ebola outbreak, began holding coordination meetings the day following the outbreak declaration and deployed a support team to Guinea two days later, on February 17.23

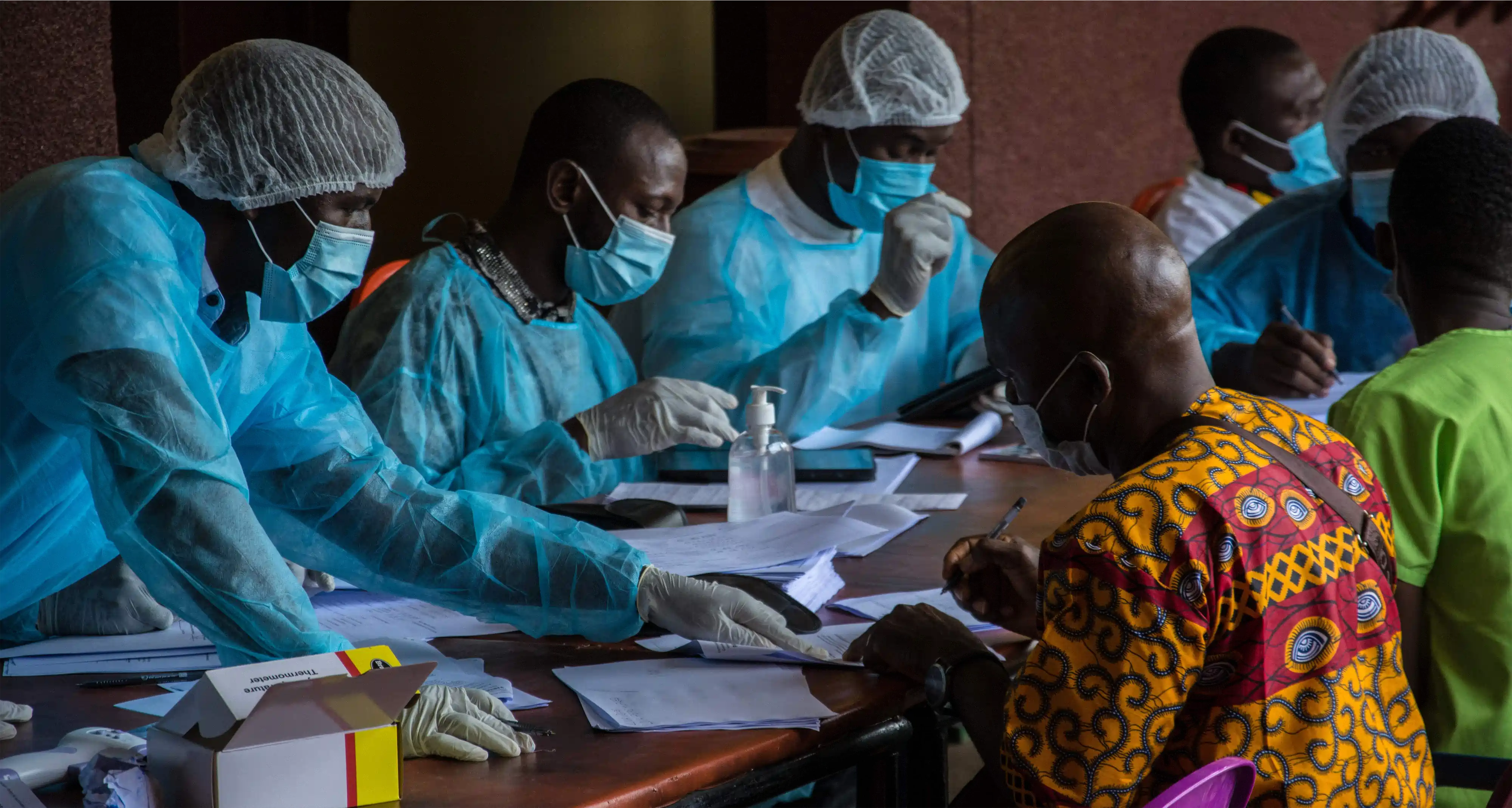

Teams of public health workers, all coordinated by ANSS, sprang into action to monitor the outbreak’s spread. More than 10,000 additional alerts of potential cases were triggered, 96% of which were investigated. More than 1,100 contacts were identified from 23 initial cases, and nearly all of them were monitored daily. Because the outbreak’s epicenter was located near the borders of Liberia and Côte d’Ivoire, officials held coordination meetings among the three countries and conducted over 2.5 million screenings at their points of entry.24 In local areas where Ebola was known to be present, officials established screening checkpoints.25

At the start of the outbreak, PCR lab capacity was expanded in N’Zérékoré, the capital of the affected region, to test for Ebola quickly and accurately—eliminating the need to send samples further afield.26 Simultaneously, genetic sequencing capabilities were enhanced in the nation’s capital of Conakry to better understand the dynamics of new cases and how they compared with past outbreaks. 27 During the 2014 epidemic, samples initially needed to be sent to France for testing—causing significant delays in disease identification. During the 2021 outbreak, laboratory confirmation took only two days, thanks to expanded laboratory capacity.

At the community level, ANSS and partners deployed 900 trained mobilizers to help prevent the spread of Ebola and support families in using safe and dignified burial practices. Two vacant infectious disease treatment centers in the region were rehabilitated to manage Ebola patients. Local health facilities were evaluated on their infection prevention and control (IPC) practices, while receiving additional training and supplies. Throughout the outbreak, nearly 11,000 people were vaccinated against Ebola, including 2,800 health care workers and others at high risk due to links to Ebola cases. 28

By the time the outbreak was declared over in June 2021, 23 cases had been identified; 12 people had died, including five health care workers.29 Although it took nearly a month for officials to detect the outbreak,30 this was a dramatic improvement from 2014, when detection took four months.31 Extensive upgrades to Guinea’s preparedness infrastructure facilitated a shorter time to detection, which was followed by a prompt and effective response that contained the outbreak, saving lives and preventing the kind of suffering and devastation experienced just a few years earlier.

Amanda McClelland, Senior Vice President of Prevent Epidemics, Resolve to Save LivesGuinea has made impressive strides to strengthen its national health security since the tragic 2014-2016 Ebola epidemic. The determination of the country’s epidemic and response leadership, with support from international partners, has dramatically changed how disease outbreaks are handled in the country

Key Preparedness Factors

- Risk Assessment & Planning

- Emergency Response Operations

- National Laboratory System

- Disease Surveillance

- National Legislation Policy & Financing

- Human Resources

- Risk Communications

2014–16 epidemic (889 days)

2021 outbreak (153 days)

Start

Detection

Verification

Control36

| 2014-2016 epidemic | 2021 outbreak | |

|---|---|---|

| Duration | 889 days | 153 days |

| Cases | 28,616 cases | 23 cases |

| Deaths | 11,310 deaths | 12 deaths |

| Cost of containing the outbreak | >$3.6 billion43 | < $100 million44 |

| Case fatality ratio | 70% | 52% |

| 2014-2016 epidemic | 2021 outbreak | |

|---|---|---|

| Coordination | 0 Emergency Operation Centers | 1 national and 38 district-level EOCs |

| Staff | Few trained field epidemiologists | 179 trained field epidemiologists |

| Lab capacity | 0 Ebola testing labs (sent to Lyon, France and Hamburg, Germany for initial testing);37 results in about 7 days38 | National and regional testing; results in about 1 day39 |

| Identification (from first known illness to laboratory identification) | 4 months after first case40 | 1 month after first case |

| Containment | Border controls weren’t activated for five months. | More than 2.5 million screenings were conducted at points of entry. |

| Vaccination | Experimental vaccine in clinical trials | 11,000 people vaccinated |

| Percentage of cases added to contact list following positive test | 28-31%41 | 39%42 |

What Happened in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC)

On September 5, 2021, a girl in North Kivu province, DRC, was admitted to a local health center with fever, headache and physical weakness. She was discharged two days later but readmitted the following week with additional symptoms, including diarrhea and vomiting. She tested positive for malaria, a common infection, and died shortly after. In the following weeks, both her father and sister fell ill and died (her sister had also tested positive for malaria). Local public health authorities were informed of the deaths on September 30, and a team was sent to investigate, but no samples were taken to test for Ebola, which had not been considered a potential diagnosis at the time.

In early October, a three-year-old neighbor of the family fell ill with similar symptoms, as well as abdominal pain, difficulty breathing and vomiting blood. He died on October 6. Samples of his blood were taken the following day and he was confirmed to have had Ebola.45 Public health authorities suspected that the outbreak had likely been spreading for some time and recognized that if it was not controlled quickly, it would expand rapidly. The disease confirmation had been complicated by co-infections of malaria and other diseases with similar symptoms, delaying the diagnosis. Ongoing violent conflict in the region made the stakes even higher.

The Response in DRC

Working with WHO and other partners, local health officials quickly took action. During and after the 2018-2020 outbreak, DRC began building its surveillance systems, training contact tracers and developing greater lab capacity—all of which improved the country’s ability to mount an effective response. The day after the new Ebola case was confirmed in October 2021, 150 contacts of the deceased had already been identified. During the course of the outbreak, authorities tracked possible cases at health facilities and elsewhere through nearly 22,000 alerts issued from across the health system, of which 98% were investigated. More than 4.7 million people were screened at points of control established to keep Ebola cases from spreading throughout DRC or beyond its borders.

Approximately 1,800 samples from suspected cases and contacts were tested for Ebola in four regional labs46 opened in response to the 2018-2020 outbreak.47 Due to expanded local testing capacity, time to test the initial samples was reduced from five days48 in 2018 to two days in 2020.49

Across the affected region, health care workers were trained and retrained in IPC measures—which keep patients and health care workers safe from avoidable infections. Training included how to screen for potential Ebola cases, and health care workers also received IPC kits with proper personal protective equipment. During the 2021 outbreak, not a single health care worker was infected.

The 2021 outbreak of Ebola in DRC was declared over three and half months after it was declared, with only 11 cases and nine deaths. The previous outbreak had taken over two years to bring under control.

For the first time in DRC, authorities had a fully licensed vaccine from the start of the outbreak. The Ebola vaccine was trialed and administered on an experimental basis during the 2014-2016 epidemic and was shown to be both safe (causing only mild side effects) and 97.5% effective.50 It was subsequently approved by Congolese regulatory authorities in February 2020 and made available for use during the 2021 outbreak.51 In DRC, nearly 2,000 people were vaccinated during the outbreak, including case contacts and frontline health care workers. Community groups led risk communication activities and promptly addressed misinformation rumors about the vaccine through targeted campaigns.

To support decision-making grounded in evidence, emergency response leaders worked on a collaborative research system to easily share information with each other about the outbreak. Participating partners conducted surveys throughout the outbreak to further inform the response. Although it took DRC’s public health system a month to identify the 2021 outbreak,52 this was half the time it took in 2018.

The 2021 outbreak of Ebola in DRC was declared over on December 16, three and half months after it was declared, with only 11 cases and nine deaths.53 The previous outbreak had taken over two years to bring under control.54 Lessons learned from the 2018-2020 outbreak laid the groundwork for the far more successful 2021 response. Surveillance and laboratory systems, IPC procedures and training, vaccine rollout and contact tracing were all dramatically expanded and improved.

Key Preparedness Factors

- Risk Assessment & Planning

- Emergency Response Operations

- National Laboratory System

- Disease Surveillance

- National Legislation Policy & Financing

- Human Resources

- Risk Communications

2018 epidemic (702 days)

2021 outbreak (103 days)

Start

Detection

Verification

Control

Bottleneck

An outbreak response is multifaceted and coordinated across a range of sectors and actors. Relative weaknesses can lead to bottlenecks that delay or otherwise impair response efforts. These bottlenecks can be identified via after-action reviews and are valuable intel for improving future response efforts.

Facilitator

A disaster never happens because a single thing goes wrong. Bottlenecks or other system weaknesses are often balanced by facilitators—factors that strengthen response efforts. Facilitators can also be identified via after-action reviews and may be the direct result of system improvements following the identification of bottlenecks.

References

- Heeney JL. (2015). Hidden Reservoirs. Nature. 527, 453-455. https://doi.org/10.1038/527453a

- Kupferschmidt K. (2021, March 12). New Ebola outbreak likely sparked by a person infected 5 years ago. Science. https://www.science.org/content/article/new-ebola-outbreak-likely-sparked-person-infected-5-years-ago

- World Health Organization. (2021, February 23). Ebola Virus Disease. https://www.who.int/emergencies-old/diseases/ebola/frequently-asked-questions

- The first such treatment approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration was released in 2020. Learn more: https://www.fda.gov/emergency-preparedness-and-response/mcm-issues/ebola-preparedness-and-response-updates-fda

- World Health Organization. (2020, February 14). Four countries in the African region license vaccine in milestone for Ebola prevention. https://www.who.int/news/item/14-02-2020-four-countries-in-the-african-region-license-vaccine-in-milestone-for-ebola-prevention

- Standley C, MacDonald P, Attal-Juncqua A, et al. (2020). Leveraging Partnerships to Maximize Global Health Security Improvements in Guinea, 2015-2019. Health Security. Jan 2020. S-34-S-42. http://doi.org/10.1089/hs.2019.0089

- Standley C, MacDonald P, Attal-Juncqua A, et al. (2020). Leveraging Partnerships to Maximize Global Health Security Improvements in Guinea, 2015-2019. Health Security. Jan 2020. S-34-S-42. http://doi.org/10.1089/hs.2019.0089

- Richardson ET, McGinnis T, Frankfurter R. Ebola and the Narrative of Mistrust. BMJ Global Health. 2019; 4:e001932. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2019-001932

- McNeil, D. (2014, August 12). Using a Tactic Unseen in a Century, Countries Cordon Off Ebola-Racked Areas. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2014/08/13/science/using-a-tactic-unseen-in-a-century-countries-cordon-off-ebola-racked-areas.html?_r=0

- Kilberg R. (2014, December 16). Building Borders around Ebola. Migration Policy Institute. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/building-borders-around-ebola

- ActionAid. (2021, February 24). Women’s Groups Lead Fight against Misinformation as Ebola Returns to DRC. https://reliefweb.int/report/democratic-republic-congo/women-s-groups-lead-fight-against-misinformation-ebola-returns-drc

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019, March 8). 2014-2016 Ebola Outbreak in West Africa. https://www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/history/2014-2016-outbreak/index.html

- Medecins Sans Frontieres. (2020, June 25). DRC’s Tenth Ebola Outbreak. https://www.msf.org/drc-tenth-ebola-outbreak

- World Health Organization. (2020, November 29). Ending an Ebola Outbreak in a Conflict Zone. https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/813561c780d44af38c57730418cd96cd

- World Health Organization. (2020, June 26). Ebola Virus Disease – African Region (AFRO), Democratic Republic of the Congo. https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/2020-DON284

- World Health Organization (2021, February 17). Ebola Virus Disease – Guinea. https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/2021-DON312

- World Health Organization (2021, February 17). Ebola Virus Disease – Guinea. https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/2021-DON312

- Keita AK, Koundouno FR, Faye M, et al. (2021). Resurgence of Ebola Virus in 2021 in Guinea Suggests a New Paradigm for Outbreaks. Nature. 597, 539–543. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03901-9

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021, September 13). Global Health Security Investments Improve Guinea Ebola Outbreak Response. https://www.cdc.gov/globalhealth/healthprotection/fieldupdates/2021/guinea-ebola-response.html

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020, December 8). Global Health Security Investments Prepare Guinea and Uganda for COVID-19. https://www.cdc.gov/globalhealth/healthprotection/fieldupdates/fall-2020/ghs-guinea-uganda-covid.html

- Key organizations included the African Field Epidemiology Network, German Cooperation, Médecins Sans Frontières, WHO Guinea Office and the International Organization for Migration.

- Delamou A, Keita M, Beavogui AH, et al. (2021). Is Guinea Meeting the Challenges to Control the New Ebola Virus Disease Outbreak in West Africa? Preventive Medicine Reports, 23, 101394. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmedr.2021.101394

- Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021, February 24). Outbreak Brief 1: Ebola Virus Disease (EVD) Outbreak. https://africacdc.org/disease-outbreak/outbreak-brief-1-ebola-virus-disease-evd-outbreak/

- World Health Organization. (2021, June 19). Ebola Virus Disease – Guinea. https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/2021-DON328

- Displacement Tracking Matrix. (2021, March 9). Guinea – Ebola Situation Report 2 (8 March 2021). https://dtm.iom.int/reports/guinea-—-ebola-situation-report-2-8-march-2021

- World Health Organization. (2021, June 19). Ebola Virus Disease – Guinea. https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/2021-DON328

- World Health Organization. (2021, June 19). Ebola Virus Disease – Guinea. https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/2021-DON328

- World Health Organization, Regional Office for Africa. (2021, June 19). Ebola Outbreak in Guinea Declared Over. https://www.afro.who.int/news/ebola-outbreak-guinea-declared-over

- Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021, June 19). Republic of Guinea Declared End of Second Ebola Virus Disease Outbreak. https://africacdc.org/news-item/republic-of-guinea-declared-end-of-second-ebola-virus-disease-outbreak/

- Resolve to Save Lives recommends a metric of 7 days. Learn more: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01250-2

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021, September 13). Global Health Security Investments Improve Guinea Ebola Outbreak Response. https://www.cdc.gov/globalhealth/healthprotection/fieldupdates/2021/guinea-ebola-response.html

- World Health Organization. (2015, September 4). Ground Zero in Guinea: The Ebola Outbreak Smoulders – Undetected – for more than 3 Months: A Retrospective on the First Cases of the Outbreak. https://www.who.int/news/item/04-09-2015-ground-zero-in-guinea-the-ebola-outbreak-smoulders-undetected-for-more-than-3-months

- Baize S, Pannetier D, Oestereich L, et al. (2014). Emergence of Zaire Ebola Virus Disease in Guinea. The New England Journal of Medicine. 371:1418-1425 https://www.nejm.org/doi/10.1056/NEJMoa1404505?url_ver=Z39.88-2003&rfr_id=ori:rid:crossref.org&rfr_dat=cr_pub%20%200www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

- World Health Organization. (2015). One Year into the Ebola Epidemic, January 2015. https://www.who.int/news-room/spotlight/one-year-into-the-ebola-epidemic

- World Health Organization, Regional Office for Africa. (2017, June 12). WHO Declares the End of the Most Recent Ebola Virus Disease Outbreak in Liberia. https://www.afro.who.int/news/who-declares-end-most-recent-ebola-virus-disease-outbreak-liberia-0

- World Health Organization. (2021). Ebola Outbreak 2021 – N’Zerekore, Guinea. https://www.who.int/emergencies/situations/ebola-2021-nzerekore-guinea

- Baize S, Pannetier D, Oestereich L, et al. (2014). Emergence of Zaire Ebola Virus Disease in Guinea. The New England Journal of Medicine. 371:1418-1425 https://www.nejm.org/doi/10.1056/NEJMoa1404505?url_ver=Z39.88-2003&rfr_id=ori:rid:crossref.org&rfr_dat=cr_pub%20%200www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021, September 13). Global Health Security Investments Improve Guinea Ebola Outbreak Response. https://www.cdc.gov/globalhealth/healthprotection/fieldupdates/2021/guinea-ebola-response.html

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021, September 13). Global Health Security Investments Improve Guinea Ebola Outbreak Response. https://www.cdc.gov/globalhealth/healthprotection/fieldupdates/2021/guinea-ebola-response.html

- Global Health Security Agenda. (2020). Strengthening Health Security Across the Globe: Progress and Impact of U.S. Government Investments in the Global Health Security Agenda. https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/Global-Health-Security-Agenda-Annual-Report.pdf

- Dixon MG, Taylor MM, Dee J, et al. (2015). Contact Tracing Activities during the Ebola Virus Disease Epidemic in Kindia and Faranah, Guinea, 2014. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 21(11), 2022–2028. https://doi.org/10.3201//eid2111.150684

- Dixon MG, Taylor MM, Dee J, et al. (2015). Contact Tracing Activities during the Ebola Virus Disease Epidemic in Kindia and Faranah, Guinea, 2014. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 21(11), 2022–2028. https://doi.org/10.3201//eid2111.150684

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2016). Cost of the Ebola Response. https://www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/pdf/cost-response.pdf

- Estimated from a few sources: $11.5m from US for both DRC and Guinea (https://www.usaid.gov/news-information/press-releases/mar-26-2021-united-states-announces-additional-8-million-contain-ebola-outbreaks); WHO said it needed $25m March to mid-May (https://www.who.int/emergencies/situations/ebola-2021-nzerekore-guinea/funding); As of mid-May, UNICEF said it needed $10m (https://reliefweb.int/report/guinea/unicef-guinea-ebola-situation-report-no-6-13-may-2021); International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies had 8.5m Swiss Francs request — for Guinea it was 3.3m Swiss Francs. (https://adore.ifrc.org/Download.aspx?FileId=472888); $15m from United Nations for DRC and Guinea (https://www.usnews.com/news/us/articles/2021-02-16/un-releases-15-million-to-fight-ebola-in-guinea-and-congo)

- World Health Organization. (2021, October 10). Ebola Virus Disease – Democratic Republic of the Congo. https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/ebola-virus-disease-democratic-republic-of-the-congo_1

- World Health Organization. (2021, December 16). Ebola Virus Disease – Democratic Republic of the Congo. https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/2021-DON351

- World Health Organization. (2019, November 5). The Day the Lab Techs Helped Change the Fate of a City in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. https://www.afro.who.int/news/day-lab-techs-helped-change-fate-city-democratic-republic-congo

- World Health Organization. (2018, August 4). 2018 – Democratic Republic of the Congo. https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/4-august-2018-ebola-drc-en

- World Health Organization. (2021, October 10). Ebola Virus Disease – Democratic Republic of the Congo. https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/ebola-virus-disease-democratic-republic-of-the-congo_1

- Woolsey C, Geisbert TW. (2021). Current State of Ebola Virus Vaccines: A Snapshot. PLoS Pathogens, 17(12), e1010078. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1010078

- World Health Organization. (2020, February 14). Four Countries in the African Region License Caccine in Milestone for Ebola Prevention. https://www.who.int/news/item/14-02-2020-four-countries-in-the-african-region-license-vaccine-in-milestone-for-ebola-prevention

- World Health Organization. (2021, October 10). Ebola Virus Disease – Democratic Republic of the Congo. https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/2021-DON351

- World Health Organization. (2021, December 16). Ebola Virus Disease – Democratic Republic of the Congo. https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/2021-DON351

- World Health Organization. (2020). Ebola Outbreak 2018-2020- North Kivu-Ituri. https://www.who.int/emergencies/situations/Ebola-2019-drc-

- Dyer O. Ebola: New Outbreak Appears in Congo a Week after Epidemic was Declared Over. BMJ. 2018; 362 :k3421. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.k3421

- World Health Organization. (2018, August 4). 2018 – Democratic Republic of the Congo. https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/4-august-2018-ebola-drc-en

- World Health Organization. (2018, August 4). 2018 – Democratic Republic of the Congo. https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/4-august-2018-ebola-drc-en

- World Health Organization. (2020, June 26). Ebola Virus Disease - African Region (AFRO), Democratic Republic of the Congo. https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/2020-DON284

- Estimates vary; sourced from: World Health Organization. (2020, June 25). 10th Ebola Outbreak in the Democratic Republic of the Congo Declared Over; Vigilance against Flare-ups and Support for Survivors Must Continue. https://www.who.int/news/item/25-06-2020-10th-ebola-outbreak-in-the-democratic-republic-of-the-congo-declared-over-vigilance-against-flare-ups-and-support-for-survivors-must-continue

- World Health Organization. (2021, December 16). Ebola Virus Disease – Democratic Republic of the Congo. https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/2021-DON351

- Estimates vary; sourced from: World Health Organization. (2020, June 1). New Ebola Outbreak Detected in Northwest Democratic Republic of the Congo; WHO Surge Team Supporting the Response. https://www.who.int/news/item/01-06-2020-new-ebola-outbreak-detected-in-northwest-democratic-republic-of-the-congo-who-surge-team-supporting-the-response

- World Health Organization. (2021, December 16). Ebola Virus Disease – Democratic Republic of the Congo. https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/2021-DON351